Kingsley Burrell, Sean Rigg, Christopher Alder, Simeon Francis, Darren Cumberbatch, Rashan Charles, Edson Da Costa, Mark Duggan, Zahid Mubarek. These are just a few of the Black people who have died at the hands of the British police in the past 20-odd years.

For Professor Kehinde Andrews, Professor of Black Studies at Birmingham City University, racism ’is not about personal prejudice, but rather is a matter of life and death’, and the way that people from Black communities are treated by the police is one of the starkest examples of the widespread racism that pervades British society.

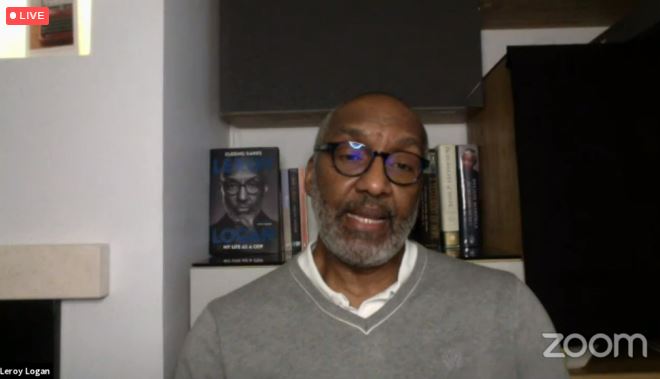

On 11 February 2021, Cumberland Lodge hosted a Cumberland Conversation with Leroy Logan, whose 30-year career was marked by a commitment to tackling this deep-seated discrimination from within the Metropolitan Police. While the conversation was informal and audience members were able to contribute by submitting questions, some of the content was anything but light: Leroy’s aim has always been to change the police ‘from the inside’.

To attempt to do his activism some justice, my focus here is on his arguments about the areas of the police where further change is needed.

Is ‘stop and search’ the way forward?

There is a valid claim that it is impossible to fully disentangle racist attitudes from the police: not least because of the entanglement of contemporary British policing and colonialism. With this history, it is no surprise that, as Leroy argued, many cops still believe extreme racial stereotypes, particularly about Black men. This plays out in many ways, but one of the current examples is the police’s ‘stop and search’ practices. Leroy argued that the prevalence of this tactic disregards what should be a key policing objective, which is to establish a ‘contract’ between police forces and the communities they serve. He noted that young people are often already scared of the police, arguing that those ’target groups aren’t going to tell police where the next stabbing will be’.

Basically, increased surveillance does not always lead to better intelligence. Leroy made a more concerning argument here too, which is that the police are ‘in denial’, because there is no evidence of a positive correlation between increased use of stop and search and reductions in levels of knife crime. The lack of evidence for the efficacy of stop and search is matched by a similar problem in relation to the war on drugs, which he argued has failed to work over the past 30 years.

Leroy’s scientific approach has led him to argue that we ‘need to look at things in the cold light of day, strip away things, do the analysis, find out what the in-built assumptions are’. For example, he was asked for his thoughts on the recent calls to ‘defund the police’. Counter to what you might imagine, for someone who is deeply committed to the police, he argued that, in the US, these campaigns offer a logical approach, although he did say he felt that the phrase ‘defund the police’ was unhelpful.

A public health approach

Leroy described the dangerous situation that happens when police – with ’uniforms and flashing lights’ – are sent to meet people who are experiencing mental health crises: this in itself can be a dangerous trigger for an individual in distress, and in some instances has led to the individual dying.

A recent article in the Guardian notes that incidents of police officers being sent to handle mental health incidents have risen by 41% in the past five years, in the UK, and an earlier article suggests that someone experiencing a mental health crisis is four times more likely to die at the hands of the police.

This lends considerable weight to Leroy’s argument that a more appropriate approach would take its cue from public health models, where the individual would initially be triaged so that a trained mental health practitioner could be sent to assist.

Making change happen

Leroy also spoke about the importance of properly monitoring and measuring areas in which change is sought. He said that much of the positive change that has happened in the police force resulted from the Macpherson review, which was commissioned following the racially motivated murder of Stephen Lawrence in 1993. Leroy argued that the emphasis of the Macpherson report on measurement was a turning point, saying that it was ’what kept the Commission to account, because what gets measured gets done’. Despite this, he was also critical of the current lack of external oversight within the police, arguing that this essentially means that everyone is ‘marking their own homework’.

There are many sites of activism, but one of the most personally challenging areas is in institutions like the police, where individuals who seek change need to continually ‘put their heads above the parapet’. Leroy hinted at his interpersonal skills when he mentioned his preference for talking assailants down rather than resorting to force. It makes you wonder how many more Black people might have died at the hands of police if it were not for police officers like him.

So, while his lucid and pragmatic arguments are impressive, what is particularly compelling is his ability to communicate these positions in a way that makes sense to people. Leroy is also now more publicly shaping the national discourse, having most recently been profiled in the outstanding Steve McQueen documentary film, Red, White and Blue. He hinted, in this Conversation, that more prominent public positions might be his next step, and Leroy seems a very strong candidate.

You can watch this Cumberland Conversation in full, here.